Exit Wounds

Independent field documentation and research initiative focused on post-conflict displacement, return dynamics, and the long-term social and political risks shaping civilian life across the Middle East and Eastern Europe.

Kamil Qadri

Kamil Qadri is a freelance journalist and the founder of Exit Wounds, an independent field reporting project focused on displacement, return, and the long political and social aftermath of conflict across the Middle East, North Africa, and Eastern Europe

His reporting centers on youth displacement and life in protracted exile, examining how post-conflict environments shape risk, opportunity, and long-term stability beyond active fighting.

Through on-the-ground interviews, documentary photography, and policy-informed reporting, Qadri connects lived experience with broader political and humanitarian dynamics. His field reporting includes work in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley on Syrian refugee return pressures and aid collapse; in Bucharest on displaced Ukrainian youth navigating education and integration in exile; and in Athens on protest movements and post-crisis political mobilization.

His work prioritizes clarity, ethical engagement, and contextual analysis, with a commitment to documenting recovery, exile, and reintegration as seriously as conflict itself.

Selected dispatches are currently under editorial review.

Qadri reporting in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley

FIELD REPORTS

Dispatch One — The Return Dilemma

In Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley, the war in Syria feels both distant and immediate. A decade after displacement, thousands of Syrians remain caught between permanence and return - raising families in tents while the idea of “home” grows abstract. With Lebanon’s economic collapse deepening and the UN promoting a voluntary return plan, refugees now face a moral and practical question: stay in exile or return to a country reborn under a new flag.

The Syrian Arab Republic no longer exists as it once did. In its place, a new government backed by regional powers is attempting to project stability - reopening schools, restoring utilities, and urging citizens to “come home.”

For those still in Lebanon, this message has found its way into conversation. The people I met spoke of this new Syria not through politics, but through the language of necessity. Their belief, or even mild trust, in this government gives it quiet legitimacy.

For Damascus, every returning family is proof that peace has returned; for those who stay, silence is its own form of resistance.

Inside Jurahiya Camp, between Bar Elias and Al Marj, I spoke with young Syrians, teachers, and families weighing that choice. Some trust the new government and plan to go back once homes are rebuilt. Others say they have nothing left to return to, no roofs, no work, and no certainty that this peace is real.

“Syria is not ready for us to go back to.” - Faraj, 23, from Aleppo

“Many Syrians still have hope. We see a real future.” - Rania, teacher at Jusoor Center

Each conversation revealed a different version of survival, shaped less by politics than by exhaustion. Between lessons, odd jobs, and the daily act of waiting, these refugees are redefining what it means to belong. Their quiet decisions - to stay, to leave, or to believe - will decide whether the new Syrian state becomes reality, or remains a promise made to the displaced.

Full dispatch under editorial review. Out soon

Jurahiya Camp, West Beqaa Valley, Lebanon · October 2025

Stability and Risk Analysis

LEBANON - October 2025

This section presents analytical context drawn from on-the-ground reporting, highlighting political, social, and stability dynamics relevant to post-conflict and displacement environments.

Overview

This assessment draws on independent field reporting conducted in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley, focusing on displacement dynamics among Syrian refugees and the implications of host-state collapse for social stability, civilian risk, and long-term political outcomes. It reflects qualitative interviews, field observation, and contextual analysis rather than predictive modeling or formal policy evaluation.

While international discussions of Syrian refugee return often emphasize conditions inside Syria, evidence from the Beqaa Valley indicates that return decision-making is increasingly shaped by deterioration within Lebanon itself. Economic collapse, shrinking humanitarian capacity, and informal coercion at the local level have transformed “voluntary return” into a constrained risk calculation rather than a genuine choice.

Key Stability Drivers

1. Host-State Collapse as a Primary Risk Factor

Lebanon’s ongoing economic and institutional collapse has emerged as the dominant driver of instability for displaced populations. Inflation, currency collapse, and the breakdown of public services have reduced the state’s capacity to provide even minimal protection or regulation. As formal governance recedes, informal mechanisms, municipal pressure, landlord leverage, employer exploitation, and localized security practices, play an increasingly central role in shaping refugee behavior.

This environment creates indirect but powerful incentives for return, even in the absence of improved security conditions inside Syria.

2. Return Pressure Without Political Resolution

Field interviews suggest that return is rarely framed by refugees as a belief in safety, reconciliation, or reconstruction in Syria. Instead, return is discussed as a last-resort response to worsening conditions in Lebanon. This disconnect between political narratives of “voluntary return” and lived decision-making increases the likelihood of premature, coerced, or cyclical movement rather than durable solutions.

The absence of credible legal, economic, or security guarantees on either side of the border sustains prolonged uncertainty and instability.

3. Youth Displacement and Long-Term Risk

Youth face a distinct risk profile. Limited access to education, legal employment, and mobility has narrowed perceived future pathways, particularly for adolescents and young adults. Many view prolonged exile in Lebanon as offering diminishing returns, while return to Syria is approached with hesitation rather than confidence.

This dynamic contributes to political disengagement, delayed life decisions, and increased vulnerability to exploitation. Over time, it risks producing a cohort shaped more by exclusion and uncertainty than by integration or recovery.

Implications for Stability

Protracted displacement under conditions of host-state collapse does not produce immediate crisis, but it steadily erodes social cohesion and predictability. Informal integration may increase at the community level, yet trust in institutions continues to decline. As humanitarian capacity contracts, civilians are pushed toward individualized survival strategies, increasing fragmentation rather than collective resilience.

The resulting environment is characterized by:

Constrained choice rather than agency

Informal coercion rather than formal policy

Long-term instability rather than acute breakdown

What to Watch

Further contraction of humanitarian assistance and its impact on return pressure

Increased localization of coercive practices at the municipal or community level

Shifts in youth decision-making around migration, work, and education

Growing divergence between international policy frameworks and lived realities on the ground

Methodological Note

This assessment is derived from original field reporting, including semi-structured interviews, observational field notes, and contextual analysis conducted during independent deployments. It does not rely on classified sources, predictive modeling, or institutional datasets, and is intended to complement rather than replace formal research and policy analysis.

Dispatch Two -“Ukraine’s Lost Generation”

Bucharest Sector IV, Romania - December 15, 2025

An on-the-ground look at how prolonged displacement is complicating post-war return and recovery for Ukraine.

Nearly four years into the war, tens of thousands of Ukrainians continue their lives outside of Ukraine. Teenagers who fled at thirteen are now applying for college; those who fled at sixteen have nearly completed bachelor’s degrees in Romanian institutions. At the start of the war, the European Union implemented temporary assistance for refugees fleeing to neighboring countries- measures such as continued education for children, community organizations, language classes, and temporary housing.

Now, after almost four years of displacement, these “temporary measures” have become permanent.

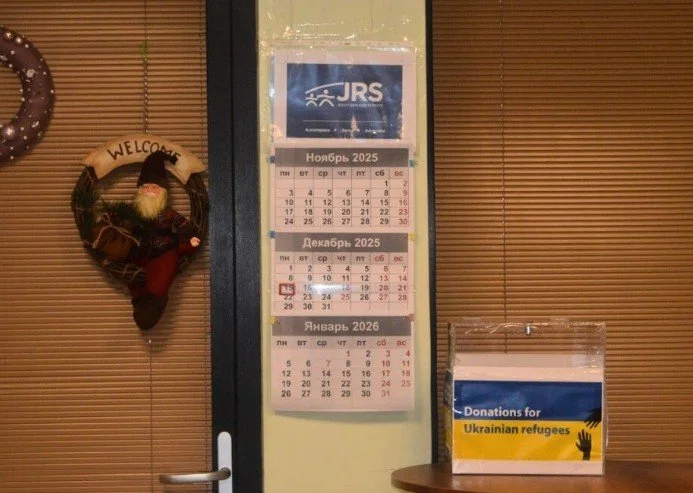

In Romania, one organization- the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS), has focused on youth education, Romanian language classes, and general integration. JRS supports Ukrainian children through a kindergarten program where they are taught Ukrainian, Romanian, and English. For older children, the organization offers music lessons as well as language classes. JRS is run by a group of Ukrainian teachers from various regions of Ukraine, all of whom escaped to Romania at different points throughout the war.

Mariia, 20, from Odesa, teaches a classroom of 25 children. She is pursuing a degree in international relations through her university in Ukraine, with classes held online. I sat down with her in Bucharest to discuss the impact of long-term displacement among young Ukrainians. When asked about her day-to-day life, she says, “Here I volunteer—I help with translations, documents, and I teach English to children.”

Her contributions stress the importance of her generation, and how Ukraine will one day call on this cohort to rebuild the country. It is not a question of if the war will end, but when it does, the eventual ceasefire will result in a mass call for return. The question now is whether they will answer.

When asked about the decision to return to Ukraine, Mariia says she does not think Ukraine will be able to reclaim everyone who grew up outside its borders. A large part of this belief is rooted in memory. Teenagers who make new friends, discover new cities, and learn new languages are inevitably drawn to the places where they associate life with friendship, laughter, and safety.

At the same time, permanent displacement has come with its own consequences.

Apartment blocks in Sector IV, Bucharest, now home to many Ukrainian refugees.

A Ukranian flag hangs behind the Jesuit Refugee Service desk, Bucharest

I spoke with Hanna, a 16-year-old also from Odesa, who has been in Romania since March 2022. She described the challenges of forced integration and her experiences with locals in Bucharest. Multiple people, she says, have told her to “go back to Ukraine.”

“There is bullying,” Hanna tells me. “Teachers say bad things. Ukrainian children are sometimes separated in class.”

Mariia also mentions cases of vandalism against Ukrainians. “Some people do very bad things,” she says. “Neighbors damage Ukrainian cars.” She declined to comment further.

I learned that some local Romanians believe Ukrainians have a better life in Romania. “They don’t understand that we also had normal lives in Ukraine,” Mariia says. Housing has also become an issue. “Sometimes one room costs twice as much just because you are Ukrainian.”

Hanna tells me about her younger sister, who attends a public elementary school. She says many Romanian teachers separate students in class, with Romanian children sitting in the front and Ukrainian students in the back. “Romanian teachers give bad grades to Ukrainian students,” she says. “This is common.”

Mariia adds that some private schools offer better environments, but the cost makes them inaccessible for many families. As a result, most Ukrainian youth continue to study in public schools across the city, navigating a system that was never designed for years of displacement.

For many Ukrainian families, exile was always imagined as temporary. Parents speak about return as an inevitability, something that will happen once conditions allow. But for their children, the calculation is different. Adolescence has unfolded elsewhere. The years that shape language, confidence, ambition, and belonging have passed outside Ukraine’s borders.

What has emerged in cities like Bucharest is not simply a refugee population waiting to go home, but a generation quietly building long-term lives. Emergency policies introduced in 2022, temporary protection, parallel schooling, short-term housing, were designed to respond to crisis. Nearly four years later, those policies form the infrastructure of everyday life. Decisions once framed as provisional- where to study, which language to learn, which qualifications to pursue- are now shaping futures that may not include return.

Ukraine’s reconstruction is often discussed in terms of infrastructure and security. Roads, bridges, power grids, and institutions will need to be rebuilt. But reconstruction also depends on people. Teachers, civil servants, planners, professionals, and young adults who will carry the country forward. Many of those people are now coming of age elsewhere.

Mariia belongs to that generation. Her education is Ukrainian. Her daily life is Romanian. Her skills, networks, and routines are being shaped outside the country that will eventually need them most.

For Hanna, the idea of return is tied to memory rather than certainty. Ukraine remains home in principle, but not necessarily in practice. “Home is home,” she says, even as she acknowledges that many people will not go back.

Others are more direct. Alena, 18, from Kherson, left Ukraine at fourteen. She arrived in Romania in April 2022. “My adolescence happened here,” she says. She has friends, a boyfriend, and plans to study music. She is learning Japanese and wants to move to Japan. Ukraine is still part of her life, but not the place where she imagines building it.

Across Bucharest, Ukrainian families live in apartment blocks that were once meant to house short-term guests. Children attend schools that were never designed for them. Community centers fill gaps left by national systems. Life continues. Time moves forward.

When the war ends, Ukraine will issue a call that will reach young people who spent their formative years in exile, who learned other languages, adapted to other systems, and built lives shaped by displacement. Some will return. Others will not.

What remains uncertain is whether Ukraine, and the policies governing displacement across Europe, are prepared for that reality. A generation raised in waiting is now growing into adulthood. Whether they see their future in Ukraine will depend not only on peace, but on whether return still feels possible, familiar, and worth the cost of leaving behind the lives they have already begun living.

Dispatch: Athens Moves as One - Inside the November 17 Polytechnic March

Riot police hold a defensive line on Alexandras Avenue as thousands of protesters pass by

Athens — The air was already heavy on Alexandras Avenue by early evening, long before the march reached the U.S. Embassy. What starts every year as a commemoration of the 1973 Polytechnic uprising has become something more layered: a test of political mood, a measure of how Greece sees its alliances, and a glimpse into which way the city’s younger blocs are leaning.More than an hour before the front banners arrived, riot police units took up positions along the perimeter streets leading to the embassy.

They stood with the practiced stillness of a force that has done this dozens of times, knowing that the march always stops here, and that everything after depends on the mood of the crowd.

By the time the first clusters of protesters reached the avenue, the crowd had thickened into thousands. Older men who lived through past marches walked alongside students who weren’t born when the first antiauthoritarian blocs took shape. Metal barricades rattled under the weight of people leaning over them for a clearer view.

The march moved in formations, not as a loose flow but as coordinated blocs. The most striking among them was a disciplined, almost paramilitary student contingent: black shirts, helmets clipped to their belts, thick wooden sticks wrapped with red flags

These blocs act as their own internal security, a hallmark of Greek protest culture. They’re loud, sharp, and disciplined, exactly the opposite of how protests look in much of the world. When they move, they move as one.

A few meters ahead of them, the lead banners stretched across the width of the avenue, held up by students stepping in time.

A tightly organized leftist student bloc marches in formation toward the police line.

What stood out this year wasn’t violence -there was none in the areas I covered- but choreography. The flow of people, the measured retreat of police lines as the march advanced, the unspoken rules between blocs and officers who have learned to read one another’s posture.

Side streets filled with families watching from a distance. Some cheered; others filmed; others simply stood with hands in pockets, taking in the spectacle as if it were a ritual, which, by now, it is.

Further behind the main blocs, the scene took on a different rhythm: marchers singing, small groups joking with one another, police walking in parallel

By the time the last groups passed the embassy perimeter, the city had quieted. Only the blinking sirens and the fading chants lingered over the avenue. For a brief stretch, Athens felt suspended - a city reenacting its past while trying to assert its present.

The November 17 march is always about memory. But after watching it up close, it’s also clear that it’s about measurement, of power, of solidarity, of who still shows up and why. And like most political rituals, the real story is in who stands in the street when the lights hit them.

MAT Police walk next to protesters, shields ready to create a barrier in an instant

Fieldwork Gallery

Selected images from the Beqaa Valley, documenting life between displacement and return.

BEQAA VALLEY, LEBANON, OCTOBER 20, 2025

FIELD NOTES

Reflections, impressions, and raw observations from ongoing reporting across Lebanon, Greece, and beyond.

Between assignments, I keep a record of what doesn’t fit neatly into a dispatch - fragments of conversation, field reflections, and moments from the road. These notes are written in real time: sometimes in airports, sometimes in camps, always in motion.

COMING SOON

Contact

For assignments, story pitches, or collaborations, please get in touch below.

𝕏 — @KamilQadri_

in — Kamil Qadri